THE PLAYERS

DAVE WINFIELD looked like a sleek panther. He was big- 6-6 and 220 pounds. But he was lithe and when he swung or threw the ball, he did it like a predator who had been waiting for precisely that moment to unveil his full power and speed.

I first heard of him as a basketball player at the University of Minnesota, where helped the Golden Gophers win their first ever Big Ten title in that sport, leading the team in rebounding. (He was also involved in the most famous brawl in college basketball history in a game against Ohio State). He was voted MVP of the college World Series- as a pitcher. Upon graduation, he was drafted by four different professional teams. One was the Minnesota Vikings of the NFL, who chose him for his size and athleticism, even though he never played football at Minnesota. The Atlanta Hawks of the NBA and the Utah Stars of the ABA both wanted him to play basketball. And the San Diego Padres wanted him to play baseball. He chose them.

First they decided to make him an outfielder to take advantage of his bat and his powerful arm in throwing out runners. Then they decided to skip the minor leagues entirely and put him right into their line- up. He hit .277 with 3 homers and no steals in 56 games. He didn’t become an immediate star. He never hit more than .283 his first five seasons and hit 76 homers in 638 games. He did manage to steal 26 bases in 1975, hit 25 homers in in 1976 and score 104 runs in 1977, but he never seemed to put it all together.

Then, in 1978 he hit .308 with 24 home runs and 21 steals, driving in 97 runs. In 1979 he upped that to .308 with 34 homers, 118 RBIs and 97 runs scored. He was finally a star. And then he wasn’t. In 1980 he hit .276 with 20 homers and 87 RBis.

But George Steinbrenner wanted to make a big splash and offered him the then richest contract in the history of baseball, $23 million over ten years, producing amazement, a lot of Steinbrenner jokes and a famous Sports Illustrated cover:

http://ecx.images-amazon.com/images/I/412SlML8l2L.jpg

But Winfield was anything but a flop as Yankee, He hit a respectable .294 with 13 homers in 105 games in the strike year, then blasted a career high 37 homers with 106 RBIs in his first full year in pinstripes, 1982, the first of five straight 100 RBI years. He followed that with 32 homers and 116 RHIs in 1983. In 1984 he was in a great battle for the batting title with teammate Don Mattingly, hitting .340. He had only 19 homers that year but had another 100 RBIs. He continued to be highly productive through 1988, which may have been his best all-around year, hitting .322 with 25 homers and 107 RBIs.

But he feuded over his contract with Steinbrenner, who somehow thought the contract was for $16 million, not $23 million. (Didn’t he read these things?) When Winfield had a poor World Series in 1981, Steinbrenner called him “Mr. May”, a reference to Reggie Jackson being called “Mr. October” for his stellar post season play. “Throughout the late '80s, Steinbrenner regularly leaked derogatory and fictitious stories about Winfield to the press. He also forced Yankee managers to move him down in the batting order and bench him. Steinbrenner frequently tried to trade him.” (Wikipedia). Steinbrenner then paid a gambler with mafia connection, Howie Spira, to dig up dirt on Winfield and got himself banned from running the team, (which allowed his baseball people to begin building the team that would win four world championships in the late 90’s).

In 1989 he missed the entire season with a back injury. One wondered if he was done at age 38. But, amazingly, he came back only to be traded to the Angels, for whom he had a couple more productive years. Then he signed with the Blue Jays at age 40 and hit .290 with 26 homers and 108RBIs, helping the Jays to win their first championship. Finally, he wound up back in Minnesota playing for the Twins for a couple of years before a brief appearance with the Indians at age 44 in 1995. He wound up with 3,100 hits and 465 home runs and drove in 1,833 runs, the 17th most in baseball history. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2001.

Bill James in his 1985 Historical Baseball Abstract: “Among the great right fielders listed here, only about a half dozen hit with more power than Winfield. Perhaps the same number can run faster. About as many had as good an arm. With his career average in the .290 range, there should be no question of Winfield’s right to stand among the greatest at this positon.

What I remember more than anything else is his line drives. People are awed by mortar shots that go high and far but even more impressive to me are the howitzer shots of big, tall athletes like Winfield. Dave’s shots go out of the park is a big hurry. They threatened to tear gloves off of fielders hands or blow holes in outfield walls even if they didn’t clear them. He was always dangerous and that made him a fascinating player to watch.

Willie Mays told a young ANDRE DAWSON to “take care of yourself- you’re the closest thing to me.” Dawson was a five-tool player who earned great respect for playing through injuries and disputes with management to have a Hall of Fame career. He had a menacing scowl at the plate and a great nickname “The Hawk”, given him by an uncle as a kid because instead of shying away from a thrown ball, he attacked it like a hawk.

He first injured his left knee playing football in high school in 1971. He had the first of more than a dozen knee surgeries at age 17. He decided to play only baseball after that. He was National League Rookie of the Year in 1977 with a .282 average, 19 homers and 21 steals. He also was a superb center fielder who would win 8 gold gloves before his knee problems returned. His one weakness was that he lacked patience as a hitter, having 30 walks and 128 strike-outs in 1978 and 27/115 the next year. Nonetheless he matured as a hitter and hit over .300 each year from 1980-82 and .299 in 1983. In those four years he hit 96 home runs, 135 doubles, 27 triples and stole 124 bases in 561 games, (per 162 that’s 28/39/7/36). He was second to Mike Schmidt in the 1981 MVP voting and to Dale Murphy in 1983.

He also developed a reputation as a generous man and great teammate, taking a particular interest in trying to get Tim Raines and Rodney Scott off drugs, (succeeding in the first case but not in the second.) Raines was so grateful he named his second son Andre in his friend’s honor.

But the notoriously bad artificial turf in Montreal’s Olympic Stadium was taking a toll on his knees. His performance declined sharply to .248 with 17 homers in 1984and improved only marginally in 1985-86. He switched to right field because it was easier on his knees. He wanted out of Montreal. The Expos wanted to keep him but at a substantial pay cut. Dawson was a free agent after the 1986 season but found no one wanted to offer him a contract. It was later determined that this was the result of collusion among to owners to kill the free agent market. Dawson very much wanted to play for the Cubs because they played on natural grass. But they refused to offer him a contract. He and his agent showed up at their spring training facility. They were there for two futile weeks before Dawson finally presented general manager Dallas Green with a blank contract he’d already singed. Green filled in the figures: $500,000 base salary with $250,000 in incentives, far under his market value based on the standards of the time.

Dawson proceeded to revive his career in Chicago, winning the National league MVP award by hitting 49 home runs and driving in 137 of his new teammates. His knees continued to trouble him, (he wound eventually having more than a dozen operations), but played for another 9 years, including 5 with the Cubs, retiring at age 42. He wound up with 438 home runs and 314 steals, one of 8 “300-300” players in baseball history. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2010. I wonder what he might have accomplished on good knees.

I remember a Sports Illustrated article that said that Atlanta Braves fans had great respect for Andre Dawson but felt he’d have to improve quite a bit to be as good as DALE MURPHY. Murphy had a strange career, coming up as a big, (6-5, 215) power-hitting catcher in His first full season, (1978), he hit 23 homers but only batted .226, striking out 145 times. He didn’t seem to have a big future. Things got worse before they got better. He developed a psychological inability to throw the ball back to the pitcher, (similar to the Mets’ Mackey Sasser a few years later). The Braves switched him to first base, where he led the league in errors. The kid could hit come but where do you put him?

Center field. How many catchers wound up playing center field? (Yogi Berra used to play left field when not catching: Craig Biggio came up as a catcher, switched to second base, then tried some outfield, including center late in his career but switched back to second). How many of those have become five time gold glove winners and two time MVPs? Just one: Dale Murphy.

He had some huge years in the pre-juiced ball/ steroids era, (more on that later). He won his first MVP in 1982, hitting .281 with 36 homers, 23 steals, 109 RBIs and 113 runs scored to go with his first gold glove. He upped all those numbers to win his second MVP the next year: .302, another 36 homers, 30 steals, (the big, hulking catcher had morphed into a 30-30 man), 121 RBIs and 131 runs scored and another gold glove. Suddenly he was universally acknowledged as the best player in the game. (I read that SI article on a plane going south to visit my retired parents. As I got up to leave, I saw Joe DiMaggio get up in first class. It occurred to me that Murphy might be the DiMaggio of his generation. )

Murphy was amazingly consistent. While Cal Ripken Jr. was starting his incredible consecutive games steak in the Al for the Orioles, Murphy had a streak of his own of 740 straight games: I remember wondering whose steak would end first. Dale played at least 154 games in every year of the 1980’s except the strike year of 1981. He had basically the same season four years in a row: .290 and a league-leading 36 homers, 19 steals, 100 RBIs, 94 runs in 1984 and .300-37-10-111-118 in 1985. He finally had a bit of an off year in 1986, hitting .265 with 29 home runs. But then hit a career high 44 homers with a .295 average, 16 steals, 105 RBis and 115 runs in 1987. I remember watching the Braves play in St. Louis and Murphy hit a ball so high and far that the announcer started saying 1000 one….1000 two…1000 three. The ball finally appeared from the top of the screen and landed a few rows from the top of the upper decked and bounced around.

Strangely, Murphy isn’t mentioned at all in Bill Jenkinson’s “Baseball’s Ultimate Power”. He’s also not mentioned in James’ 1985 HBA. In the 2000 update, he simply says Murphy would make his “all tall team” at center field. His image seems to have faded over the years. Part of the reason is that Murphy faded. He was 31 years old in 1987 but never had another season that good. He never hit higher than .266 and never had more than 24 homers as injuries caught up with him. He also struck out a lot and players that strike out a lot often don’t age well: they have trouble making adjustments. The Braves were terrible for most of his career. They did manage to win the NL East in 1982 but got swept in the playoffs by the Cardinals. It’s hard to get recognition on an also-ran.

Maybe his biggest ‘problem’ is that he was totally uncontroversial. He was a Mormon and loved to spend time at home with his family. “Murphy did not drink alcoholic beverages, would not allow women to be photographed embracing him, and paid his teammates' dinner checks as long as alcoholic beverages were not on the tab. He also refused to give television interviews unless he was fully dressed.” (Wikipedia) He just didn’t make the headlines most modern superstars get their “recognition” from.

Dale Murphy had more total bases than any other major league baseball player of the 1980’s. He was second in home runs and RBIs. He and Roger Maris are the only two time MVPs not in the Hall of Fame. He’s often compared to Chipper Jones, who followed him as the Braves’ star. It will be interesting to see how long Chipper has to wait to get into the Hall. Dale’s manager, Joe Torre said: ““If you’re a coach, you want him as a player. If you’re a father, you want him as a son. If you’re a woman, you want him as a husband. If you’re a kid, you want him as a father. What else can you say about the guy?”

CAL RIPKEN had no trouble getting recognition. He was rookie of the year his first full season, (1982), hitting only .264 but with 29 homers, 93 RBIs and 90 runs scored, (he was never much of a base stealer). What increased his value was that he was a shortstop- and a good one. Bill James: ”Under-rated as a defensive player because he doesn’t fit into the Ozzie Smith-Luis Aparicio image of a shortstop, (Ripken was 6-4 225),…Ripken had the best arm I ever saw on a shortstop. “ Young Cal upped his production the next year to .318 with 211 hits, 47 doubles, 27 home runs, 102 RBI and 121 runs scored. He won the MVP and the Orioles won the World Series.

But what he became famous for was his presence on the field. Not his “stage presence”, although he had that. He just never came off the field. Everybody knows that from May 30, 1982, through September 19, 1998 Cal Ripken Jr. played in a major league record 2,632 consecutive games. What some may not know tis that he began that streak playing an incredible 8,243 consecutive innings that ended when his own father, Cal Sr,. took him out of a game on September 14, 1987. Cal broke Lou Gehrig’s legendary mark of 2,130 consecutive games on September 6, 1995, the celebration for which has been credited with returning baseball to a grudging popularity after the 1994-95 strike, in part because Ripken was viewed as a clean, uncontroversial player and an appropriate hero for young people. (Why didn’t that work for Murphy?)

Ripken had some other great seasons: .304 with 27 homers in 1984; 110 RBis and 116 runs scored in 1985; .323 with a career-high 34 home runs and 114 RBIs in 1991, bringing him a second MVP; .315 in 1994 and .340 in 1999. But he also had some off years, hitting between .250 and .257 six times and having seasons where he hit 13, 17, 17 and 14 home runs. Players who have had long consecutive game streaks, (Gehrig, Billy Williams, Steve Garvey), have usually been very consistent offensive performers. Ripken was not. He wound up with great career totals: 431 home runs, 3,184 hits 1,695 RBIs and 1,647 runs scored. But why didn’t he consistently perform at his 1983 and 1991 level?

No doubt Ripken had many small injuries that might have reduced his level of performance during his streak but we know he didn’t have any major debilitating injuries or the streak would have ended. The other players with long steaks tended to be first basemen or outfielders. The wear and tear is likely less at those positons than it is at shortstop or third base, which Ripken started playing in 1996. But I think the big reason is the same thing that impacted Carl Yastremski: Ripken was famous for changing his stance constantly. When they were planning a statue in his honor, they had a hard time deciding what stance to depict him in. Everything in sports is done from the ground up: if your base isn’t set or isn’t consistent, you aren’t going to be consistent, either.

DARRELL EVANS was born May 26, 1947 in Pasadena, California. He was 6-2 and weighed 200 pounds. He played major league baseball from 1969-1989, hitting only .248 lifetime but with a .261 on-base percentage because he averaged 97 walks per 162 games. He also hit 414 home runs and slugged .431.

DWIGHT EVANS was born November 3, 1951 in Santa Monica, California, (which is 25 miles from Pasadena). He was 6-2 and weighted 205. He played major league baseball from 1972-1991, hitting only .272 but with an on-base percentage of .370 because he averaged 86 walks per 162 games. He also hit 385 home runs and slugged .470.

For decades, I assumed these guys were brothers. You probably did, too. They even looked somewhat alike, except for Dwight’s moustache:

Darrell:

http://www.tradingcarddb.com/Images/Cards/Baseball/62037/62037-3Fr.jpg

Dwight:

http://fenwayparkdiaries.com/best players/dwight evans1.jpg

Imagine my shock when I found out they were not, in fact, related. Maybe they should adopt each other.

Bill James considers Darrell the most under-rated player in baseball history. In his New HBA, he lists 10 things that can cause a player to be under-rated and Darrell met 7 of the criteria: he was a good all-round player but not great at one thing. His batting average was low, even though his on base and slugging percentages were not. He didn’t get to play for a championship team until age 37 and then had an off year. He never played in New York or Los Angeles. He was “not notably glib or quotable”. A big chunk of his career was played in “one of the worst hitter’s parks in baseball: Candlestick Park in San Francisco. He played for three different teams and played two different defensive positons, (third and first base). I’ll add that he was a contemporary of the best third baseman even, Mike S chmidt, who was in the same league. All of it kind of blurs his image. James goes to some length to demonstrate that Evans was superior to his contemporary, Tony Perez, who played the same two positons for the same number of teams but was a significant part of the best team of his time and is, unlike Evans, in the Hall of Fame, as a result. He had two 40 home run seasons, a dozen years apart, one in Atlanta in 1973 and one in Detroit in 1985, making one wonder what he might have accomplished if he wasn’t stuck in San Francisco for all those years. Evan’s nickname was “UFO because he believed in them and claimed to have seen one. He also hit a few of them.

Dwight Evans was the long-time right fielder of the Boston red Sox, overshadowed by having Fred Lynn in center field and Jim Rice in left. His best seasons, (.305 34HR 123RBI 109RS in 1987), weren’t quite as good as theirs (Lynn in 1979: .333 39HR 122 RBI 116 RS, Rice in 1978: .315 46HR 139RBI 121RS) but they were close and Evan’s 8 gold gloves were twice as many as Lynn’s and infinitely more than Rice. And “Dewey wound up with more home runs, (385 to 382 for Rice and 306 for Lynn). Evans also was late bloomer while Lynn and Rice were stars as soon as they showed up. Evans best years were when he was 29, 30, 32 and 35. He shares that trait, as well with Darrell whose best stretch came when he was 37-39. Bill James: "Dwight Evans is one of the most underrated players in baseball history." Just like his ‘brother’ Darrell. Neither is in the Hall of Fame.

Dwight Evans also earned a lot of respect for his personal qualities. SABR: “Others have suggested that Dwight Evans is already in another very special hall of fame for fathers. He and his wife Susan (Severson) met at Chatsworth High School and married at age 18. They have a daughter, Kirsten, and two sons – Tim and Justin – both of whom have suffered from neurofibromatosis, a condition described as "a sometimes disfiguring genetic disorder characterized by soft tumors, usually benign, that grow on the nerves."7 Tim, their first-born, had already undergone 16 surgeries by the age of 16. He lost one eye. The pain throughout is said to be excruciating. Their lives have been a struggle, but Susan Evans said the family is a strong one: "The No. 1 thing, Dwight and I have always had each other."8 The couple bore the burden privately. Jim Rice, who played in the same outfield with Evans for so many years, hadn't learned about their children's condition until around 2008. Evans had gone public, to help fund efforts for research and treatment. He said he "would have traded his talent and fame in a heartbeat to have spared his boys."

One day in the early 1980 I was looking through a brand new copy of “Who’s Who in Baseball I had just purchased and the movie-star handsome face of PAUL MOLITOR attracted my attention:

http://cdn1.bloguin.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/106/2013/05/molitor.jpg

So did his numbers: He’s batted .273 as a rookie but with 30 steals, (this in an era where you could become a star by stealing bases), then hit .322 with 33 steals and 16 triples his second season. He was 23 years old. Imagine being that young, that talented and that good-looking!

He missed 51 games the next year but still batted .304 with 34 steals. He also had a great percentage of successful steals, being thrown out only 7 times. Not only was he young talented and good looking but he was smart an opportunistic, too. But he kept getting hurt. He missed another 44 games in 1981, not even counting the strike and hit only .267. But he came back strong in the Brewer’s pennant year of 1982, hitting .302 with 57 extra base hits, 41 steals, (in 50 attempts) and scoring an incredible 136 runs. I christened him “Meteor Molitor”, for his speed, talent and early success. He became my favorite player, at least of those not playing for a team I was actually rooting for and I always checked his numbers in the Sunday paper.

Those numbers went down a bit the next year, (.295, 49XBP, 41 steals, 95 runs scored). Then, in 1984, the Meteor crashed, his season ending after 13 games in which he hit .217. It turned out he has another remarkable characteristic”: a remarkable ability to injure himself. In 1980 it was a pulled muscle in his rib cage, in 1981, an ankle, in 1984 a torn MCL in his elbow, which put him on the table for Tommy John surgery. It was while he recovering from this that the scandal struck. Molitor’s name came up in the trail of a drug dealer, who claimed to have been Molitor’s supplier of cannabis and cocaine. I’m an old movie buff and in the 1949 film, “Knock on Any Door”, another very handsome guy, John Derek, plays a young punk whose philosophy was ”Live fast, die young and leave a good-looking corpse”. Paul Molitor almost did exactly that.

SABR: “When he failed to turn up at his parents’ home on Christmas morning, they began to worry. His fiancée, Linda, knew Molitor was at Simon’s—his agent was out of town in Florida—and went over to rouse him for the party. The door was locked, and she received no response to her banging on the door. It turned out that Molitor had hosted a wild cocaine-heavy party the night before and was still passed out. After this sorry episode Linda threatened to leave Molitor, and Molitor himself recognized the depths to which he had fallen….Molitor resolved to quit the drug and credited his success to his faith. “I believe that God answered my prayers and gave me the strength to fight the addiction and finally to stop using cocaine.” Wikipedia: "There are things you're not so proud of — failures, mistakes, dabbling in drugs, a young ballplayer in the party scene. Part of it was peer pressure. I was young and single, and hung around with the wrong people... You learn from it. You find a positive in it. It makes you appreciate the things that are good."

So Paul had the challenge of rehabilitating his body, his life, his career and his image. He hit a grand slam. He came back in 1985 to play 140 games, hit .297 with 41 extra base hits, steal 21 bases and score 93 runs. Then he missed 57 games in 1986 due to a hamstring injury. Then, in 1987 he had his career year, hitting .353 with 62 extra base hits and steals that led to 114 runs. The amazing thing is that he did that in only 118 games as he again tore a hamstring. Over 162 games at that he’d have had 85XBH, 62 steals and 157 runs scored. He also had a 39 game hitting streak, the longest in the major leagues after Pete Rose’s 44 game streak. He was on deck when Rick Manning got a game-winning hit for the brewers in the game where the streak stopped and the fans actually booed Manning.

In his first 9 seasons he’d hit .300 just three times, despite his speed and talent. 1987 was the first of 9 seasons of his last 12 in which he hit .300, in six of which he hit over .320. He also became a durable player, playing over 150 games 6 times, aided by his mangers who tired him at various positons to avoid injuries and finally made him into a DH. After years of starring for mediocre Brewers teams, he was allowed at age 36 to seek employment elsewhere. He chose the defending World Series champion Toronto Blue Jays and had another superb season with the, , hitting .332 with a career high 22 home runs, 22 steals, 11RBIs and 121 runs scored as the Blue Jays won another title and the meteor got himself a ring. He’d been on base when Joe Carter hit his championship winning home run.

Later he returned to his native Minnesota to finish out his career. In 1996, the season he turned 40, he hit .341 with 225 hits, the most ever by a 40 year old player and 113 RBI’s on only 9 home runs, the last player to get 100 ribbies on single digit home runs. He also got his 3,000th hit, the only triple to be a #3000 hit, appropriate for this combination of talent and speed. In 2004 he was inducted in the Hall of Fame. Ted Williams compared him to Joe DiMaggio, calling him “One of the greatest right-handed hitters I’ve ever seen”. Sparky Anderson said “He’s what I call a winning player, like Joe Morgan. They’re just winners.”

When Molitor was signed by the Brewers in the first round of draft in 1976 “After the draft the Brewers invited their new phenom to Milwaukee County Stadium for the VIP treatment. While wearing a suit that was “way too big, I’m totally geekish,” Molitor met some of the players in the dugout. At one point he was sitting next to shortstop ROBIN YOUNT, only 22 years old but already in his fourth year as a starter. Veteran third baseman Sal Bando stopped by and threw Yount an outfielder’s glove, telling him, “Well, I guess this will be your last year at shortstop, kid.” Molitor remembered acute embarrassment at the whole proceeding and just wanting to get away.”

Young was a prodigy, big leaguer at age 18. He did actually play 64 games in the minor leagues for Newark of the NYP league but started for the big club the following spring. The Brewers 1973 shortstop, Tim Johnson, had hit .213 with no home runs in 136 games and Manager Del Crandall figured the kid could do as well and begin his development in the big leagues all the earlier. He was the youngest player in the majors two years in a row. I remember Yount getting a lot of initial publicity because of his age but then fading into the background for several eyars because his stats were mediocre or less: .250 with 3HR his first eyar, then .267/8HR, .252/2HR, .288/4HR, .293/9HR, .267/7HR. He was a big leaguer and apparently a pretty good shortstop but nothing special. There was talk about moving him to center field when the more promising and glamorous-looking Molitor was ready.

Bill James: “In 1978, after Yount had been in the major league for four years, he held out in the spring, mulling over whether he wanted to be a baseball player or whether he really wanted to be a professional golfer. When that happened, I wrote him off as a player who would never become a star. If he can’t even figure out whether he wants to be a baseball player or a golfer, I reasoned, he’s never going to be an outstanding player…..But as soon as he returned to baseball, Yount became a better player than he had been before: his career got traction from the moment he returned. What I didn’t see at the time was that Yount was in the process of making a commitment to baseball. Before he had his golf holiday, he was there every day, he was playing baseball every day but on a certain level, he wasn’t participating: he was wondering whether this was really the sport he should be playing. What looked like indecision or sulking was really the process of making a decision.”

Another decision he made was to start lifting weights: he was one of the first players to try this. Previously it had bene tho0ught that lifting weights would make a player too musclebound. He proved that wrong and had a break-out season in 1980, his 7th big league season, (during which eh turned 25). He hit .293 with 49 doubles, 10 triples, 23 home runs and 20 steals, driving in 87 runs and scoring 121 more. He like so many players never got much going in the strike year of 1981 but came roaring back in 1982 to win his first MVP with .331BA 46D 12T 29HR 114RBI and 129RS. That was his peak but he settled in to be a .300 hitter or close to it with good power, a lot of RBH and some steals. “Yount collected more hits (1731) in the decade of the 1980s than any other player.” (Wikipedia)

In 1985, he moved to center field after all due to a shoulder problem, (I guess a throwing arm is less important there than at a shortstop). He won a second MVP< somewhat controversially in 1989. He had hit .318 with 38D 9T 21HR 19SB 103RBI and 101RS while Ruben Sierra of Texas had .306BA 35D 14T 29HR 8SB 199RBI 101RS. Neither team was in contention. Yount was a center fielder, Sierra a right fielder. Sierra and his fans complained that Yount won the MVP because he was the right color. Who knows? Yount became the first two time AL MVP since Mantle and Marris. Yount retired four years later with 3,142 hits, 960 of which were for extra bases. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1999, to be joined by Molitor in 2004. Sometimes It just takes young men time to decide what they want to do with their life.

RYNE SANDBERG was another good-looking guy who came up as a middle infielder, (and stayed there), and another guy who left the sport for a while. He was also a combination of power and speed and all-around baseball talent. Bill James, who cedes this duty to his wife, listed him as one of the three best looking players of the 1980’s, (Mrs. James somehow didn’t list Molitor).

https://aaronmilesfastball.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/ryne_sandberg.jpg

“Ryno” was a Parade All-American quarterback who had signed a letter of intent with Washington State when the Phillies drafted him and he opted to play baseball. He reached the big club in 1981 but hit only .167 and was traded to the clubs. He was traded into the Cubs, a throw-in in a trade of shortstops: Larry Bowa doe Ivan DeJesus. James calls it a classic example of a team not knowing the value of a player and letting another team have him without much thought.

His first season in Chicago he hit .271 with 45 XBH, 7 of which were homers, 32 steals and had 54 RBIs with 103 runs scored. He was 22. James uses him as an example of trying to estimate the Hall of Fame potential of young players. He found 15 second basemen who had similar seasons at that age and 3 of them were Hall of Famers, although one, Pete Rose went on to play other positons and 3-4 other outstanding players. He found 58 players with a similar number of “win shares” at that age. 9 were in the Hall and “several more will be in the Hall in 20 years.” At the same time, Steve Sax and Johny Ray had almost the same seasons in the same year. “You could certt5ianly eli9mnate or almost eliminate Ray as a potential star because he was three year solder than Sandberg and Sax, an immense negative factor in assessing his future. …Sax was a cut-up. He had a cheeky, class-clown personality, a smart guy and a smooth talker but perhaps with a little more humor than was helpful. Guys like that rarely become superstars. …What separates Sax is that he sometimes sought attention by charm, wit and personality, as opposed to accomplishments. This would be unusual for a superstar.”

In an article on brooks Robinson, James discusses what kind of player does become a superstar. “Durocher’s law, that nice guys finish last may well be true of managers but is almost certainly not true of players. It is kind of striking, in fact, how many unusually nice people you can find among the top ten players at a positon. It also seems that if you took a team of the best player at each positon that everybody would describe as a nice guy and a team of the best player at each positon that nobody would describe as a nice guy, the nice guys would clean their clock…..The more defense is required of a positon, the more nice people seem to congregate there….defense by its nature, is a selfless, team-oriented skill while hitting is a glamour job. Thus,, it is perhaps natural that defensive positons would attract and develop players whose focus extended beyond their self-interest, while hitting spots would appeal more to people who were looking out for number one. James lists Sandberg with Charlie Geiringer, Napoleon Lajoie and Eddie Collins as second basemen with “nice guy” images and Paul Molitor as one of the third basemen, (one of his several positons) with the same. Maybe it helps to be good-looking and talented. You get a lot of positive reinforcement that way.

The Cubs started Sandberg at third but moved him to second base in 1983. Sandberg was a superb defensive second baseman. James notes that Sandberg and Tommy Herr have the best fielding percentages of any second basemen of the era, (.989) and both have the biggest gap between their percentage and the average for their positon, (.981) of any player of the era. Sandberg committed 42% fewer errors than the average second basemen. He set a record with 123 consecutive errorless games at second base and won 9 gold gloves.

But he could hit, too. His breakthrough season as a major star was 1984, the year the Cubs reached the post-season for the first time in 39 years by winning the NL East. On June 23rd, the Cubs played the Cardinals, two years removed from their 1982 championship and who would win the pennant the next year. Everybody knew they were true contenders. People didn’t know about the upstart Cubs.

Wikipedia: In the ninth inning, the Cubs trailed 9–8, and faced the premier relief pitcher of the time, Bruce Sutter. Sutter was at the forefront of the emergence of the closer in the late 1970s and early 1980s and was especially dominant in 1984, saving 45 games. However, in the ninth inning, Sandberg, not yet known for his power, slugged a home run to left field against the Cardinals' ace closer. Despite this dramatic act, the Cardinals scored two runs in the top of the tenth. Sandberg came up again in the tenth inning, facing a determined Sutter with one man on base. As Cubs' radio announcer Harry Caray described it: “

here's a drive, way back! Might be outta here! It is! It is! He did it again! He did it again! The game is tied! The game is tied! Holy Cow! Listen to this crowd, everybody's gone bananas! What would the odds be if I told you that twice Sandberg would hit home runs off Bruce Sutter?”

The Cubs went on to win in the 11th inning. The Cardinals' Willie McGee, who hit for the cycle, had already been named NBC's player of the game before Sandberg's first home run. As NBC play-by-play man Bob Costas (who called the game with Tony Kubek) said when Sandberg hit that second home run, "

Do you believe it?!" The game is sometimes called "The Sandberg Game".

Sandberg went on to hit .314 with 200 hits, 36 doubles, 19 triples, 19 homers and 32 steals, a triple and home run short of becoming the rid man in big league history to have 20 or more doubles, triple, homers and steals in a season. He drove in 84 runs battling #2 and scoring 114 runs and was named league MVP.

He had basically the same year in 1985 except he hit 26 home runs and stole 54 bases. He didn’t maintain that level of production but was still excellent for a middle infielder. Then he really found his power stroke in the late 80’s, hitting 30 homers in 1989 and leading the NL with 40 in 1990. He hit 26 homers and batted around .300 the next two years, then signed was at that time the richest contract in baseball history, 28.4 million over 4 years. His performance sharply declined after that and she shocked baseball by announcing his retirement on June 13, 1994. Sandberg said at the time: “The reason I retired is simple: I lost the desire that got me ready to play on an everyday basis for so many years. Without it, I didn't think I could perform at the same level I had in the past, and I didn't want to play at a level less than what was expected of me by my teammates, coaches, ownership, and most of all, myself.” Two months later a strike ended the season. I remember hearing rumors that Sandberg quit because he was disgusted by the argument over money in baseball. Baseball Refernce.com has a different story: “His marriage was falling apart and he tried to save it by putting a term to his nomadic ballplayer's lifestyle, but was unsuccessful. He came back in 1996 with a renewed interest in baseball, hitting 25 home runs that year. He retired after the 1997 season.” He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 2005.

WADE BOGGS and TONY GWYNN were equivalents of each other in each league. One thing I did not like about the “neutral period” of the 1970’s and 1980’s in which baseball was fully integrated with a live but not juiced ball, full development of minor leagues and bullpens and played mostly suburban ballparks with regular dimensions, (the only outlier being artificial turf, which has since been phased out), is that there was a divergence of hitters for average and for power. Guys like Mike Schmidt and Reggie Jackson would lead the league with 40 homers but hit .260 and strike out 150 times. Guys like Rod Carew, Bill Madlock in the 70’s and Boggs and Gwynn in the 80’s would hit .350 and win the batting title but with single digit home run totals. I remember thinking back to Mays, Mantle and Aaaron and, before that DiMaggio, Williams and Musial and wondering why we didn’t have players who could hit for both average and power like the old days.

That said, Boggs and Gwynn did put up impressive numbers. Boggs got most of the press in the 80’s, Hitting .349/.361/.325/.368/.317/.363/.366/.330 and winning 5 batting titles while Gwynn hit .289/.309/.351/.317/.329/.370/.313/.336 with four batting titles. That left Boggs at .352 for the decade and Gwynn .332. Boggs walked far more than Gwynn and had a considerably higher on base percentage at this point, .443-.389. Both exceeded single digits in homers once in the decade: Tony hit 14 in 1986 and Wade 24 in 1987, when the ball did seem to be juiced. But neither was a home run hitter: Wade had 64 in the decade, Tony 45. But Wade was a doubles machine: 317 to 196 for Tony. Tony led in triples with 51-36. Wade slugged .480 to .437. Gwynn, in his early years had more speed and was probably a better athlete, (he was a highly regarded point guard for San Diego State’s basketball team in his college years). Tony stole 213 bases in the 1980’s. Wade stole 24 in his entire career- in 59 attempts. Using my stat, “bases produced”, Wade had 2,943 to 2,378. Neither drove in 100 runs in the 80’s. Wade scored over 100 runs seven years in a row. Tony did it twice. For the decade, Wade produced 1,282 runs and Tony 978. Wade was slightly more durable, playing 1,183 games to 1060, (both came up in mid-season 1982. Wade produced 2.49 bases and 1,08 runs per game. Tony produced 2.24 bases and 0.92 runs per game. Both fielded their positons well but Tony wound up his career with more Gold Gloves- 5 as an outfielder to 2 as a third baseman for Wade. It probably helped Wade ot play in Boston, rather than San Diego but in the 1980’s, Wade Boggs was the better player.

Then Boggs’ career hit some bumps in the road. It was revealed that he’d had an affair with a woman named Margo Adams and, according to Baseball reference.com, “He admitted that he was a "sex addict". Boggs' "Delta Force" plan was used to film his teammates while they were cheating on their wives as blackmail to keep his clandestine relationships secret.” This over-shadowed his on the field achievements. He started missing more games, playing in 1,257 in the 1990s, (and he played to the end of the decade). He hit .300 seven more times but also had a .259 year and hit .304 for the decade. He produced 2,557 bases (2.03 per game) and 1,127 runs (0.90). He never won another batting title and never again scored 100 runs in a season. . He also didn’t stay with his original team, becoming the umpteenth Red Sox to jump to the Yankees in 1993. I still remember him riding around on a police horse in Yankee Stadium after they beat the Braves in 1996. He finished his career playing for his hometown team, Tampa Bay and got his 3,000 hit there, the only 3,000th hit that had been a home run to that date. He wound up batting .328 lifetime with 757 extra base hits and those 24 steals.

The big headlines in the 90’s belonged to Tony Gwynn, who played through 2001 and hit over .300 every year from 1983-2001, including an amazing run from 1993-1997 when he hit .358/.394/.368/.353/.372, winning batting titles the last four of those years to give him 8 for his career, tying him for second place, (with Honus Wagner) behind Ty Cobb for the most ever. That .394 in the strike-shortened year of 1994 was the highest major league average since Ted Williams’ .406 in 1941. For the 90’s, Tony played in 1,273 games , hitting .344 for the decade and producing 2,859 bases (2.25 per game), and 1,430 runs (1.12). He stayed in San Diego and became the face of the franchise, although he never played on a World Series winner and could have made more money by moving elsewhere. He was playing for his hometown team all along. That helped his image and he became a beloved player, especially when he developed mouth cancer from his use of chewing tobacco and died of it at the early age of 54 in 2014.

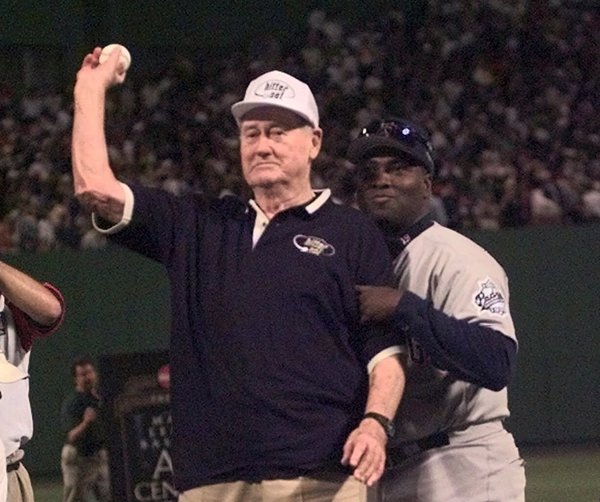

Whatever their similarities and differences, both Boggs and Gwynn were first ballot Hall of Famers, Wade in 2005 and Tony in 2007. I think Wade at his peak was a better player because of his walks and the runs he scored. But Tony had the better career and was the more highly regarded man. Ironically, it was Gwynn who sought out the advice of Ted Williams and became close friedns with him, such that Tony was the one who was at aged and ailing Williams’s side when Ted threw out the first pitch at the 1999 All-Star Game when it was held at Fenway Park, where Boggs had gotten so many of his hits.