SWC75

Bored Historian

- Joined

- Aug 26, 2011

- Messages

- 32,526

- Like

- 62,727

“PERENNIAL DISAPPOINTMENTS”

The 1960’s have been described as the “Second Dead Ball Era” because of the low scoring. But it wasn’t caused by a deadened ball. It was caused by an enlarged strike zone and a raised mound, both changes made at the insistence of Commissioner Ford Frick, who was afraid that expansion, (both of teams and the length of the season), would result in “phony” record breaking. Instead, it plunged baseball into an era of anemic offense, just at the time when pro football was beginning to get a mass audience and challenge baseball’s status as the “national past-time”. It was really the Ford Frick Era.

As I mentioned in my last article, Bill James did an extensive study of what Willie Davis’ numbers actually were over the course of his career and what his numbers would have bene in a statistically average year. Let’s look at his numbers in the 1960’s, (full seasons only), both the actual numbers and the “James numbers”:

1961 Actual: .254BA .451SP 192BP 89RP James: .256BA .453SP 193BP 89RP

1962 Actual: .285BA .453SP 346BP 167RP James: .299BA .474SP 369BP 189RP

1963 Actual: .245BA .365SP 238BP 111RP James: .266BA .396SP 266BP 136RP

1964 Actual: .294BA .413SP 317BP 156RP James: .323BA .455SP 364BP 198RP

1965 Actual: .238BA .346SP 232BP 99RP James: .265BA .386SP 269BP 126RP

1966 Actual: .284BA .405SP 289BP 124RP James: .306BA .438SP 322BP 150RP

1967 Actual: .257BA .367SP 258BP 100RP James: .293BA .418SP 316BP 138RP

1968 Actual: .250BA .351SP 293BP 110RP James: .298BA .376SP 343BP 167RP

1969 Actual: .311BA .456SP 284BP 114RP James: .329BA .483SP 309BP 130RP

(BP and RP are my numbers: runs and bases produced, based on the actual and James numbers)

James: “The essential point I am making is this: Willie Davis, throughout the 1960’s was regarded as a huge disappointment, a player who never played up to his perceived ability…The is completely unfair. Willie Davis was a terrific player. True, he didn’t walk and he was a not particularly consistent but his good years, in context, are quite impressive. The Dodgers won the pennant in 1963, 1965 and 1966 and one of the key reasons they did was because they had Willie Davis. He should not be regarded as a failure, merely because he had to play his prime seasons in such difficult hitting conditions.”

James does something similar with other players who hit the big leagues in the 60’s, although not in as much detail. He talks about Pete Ward, who it .282 with 23 homer runs and 94RBI in 1964. In a normal context, that would be .298-25-107. In the 1990’s he would have hit .332 with 29 homers and 137 RBI. Tom Tresh “in 1968 hit .233- yet he was as valuable in that season as Ed Delahanty was in 1894, when Delahanty hit .407 or as Joe Medwick was in 1938, when Medwick hit .322 with 21 homers, 122 RBI or as Albert Belle was in 1996 when Belle hit .274 with 45 doubles, 30 homers and 116 RBI.” In his article on Vada Pinson he says: The pitchers took control of the game in 1963, cutting into everybody’s numbers and making ‘perennial disappointments’ of many of the young players of that era, including Willie Davis, Frank Howard, Tom Tresh and Norm Cash.”

All kinds of such comparisons like that can be made. The point is, the players of the 60’s are as under-evaluated due to their numbers as the players of the 90’s tend to be over-evaluated due to their numbers.

One of my favorite comparisons is between the American League, which hit a cumulative .230, to the National League of 1930 that hit .303. The 1930 National League Batting champion was Bill Terry, who hit .401, the last National League .400 hitter. In 1968 Carl Yastremski won the American League with a batting average 100 points less than that, .301. Was Yaz really 100 points worse than Terry? I think we can assume that if HIS league had hit .303 instead of .230, Yaz would probably have hit something like .374 and that if Terry’s league had hit .230, Terry would have hit more like .328. Terry was still better but by 27 points, not 100.

Of course, the pitchers had a golden era. In fact, they were the real stars of the era. Sandy Koufax was probably the most admired player in the game in the mdi 60’s. From 1962-66 he won 111 games, lost 34, struck out 1,444 batters, allowed 1275 baserunners and 298 earned runs in 1377 innings, giving him a “WHIP” of 0.926 and an ERA 1.95- for FIVE years! He also pitched 4 no-hitters, one of which was a perfect game. An even bigger sign of the times was that he completed 100 out of 314 starts- nearly 1/3 and threw 33 shut-outs. He retired at age 31 because of an arm problem that I’ve read could easily have been fixed today.

His great rival for much of the decade was San Francisco’s Juan Marichal, who won over 20 games six times and over 25 games three of those times. After Koufax retired and the Giants faded, the big name was Bob Gibson of the Cardinals, who won over 20 games five times for a team that won three pennant and two World Series. Marichal in his career went 243-142, Gibson 251-174, yet it is Gibson who is best remembered today, probably because the Giants kept finishing second to the Dodgers and Cardinals, winning the pennant only in 1962, a year when Marichal, just beginning to establish himself, went only 18-11 and the Giant s lost the series.

1968 was a pitcher’s paradise Gibson set a record for the lowest ever ERA, (depending on your limit for innings), of 1.12. He had 13 shut-outs. Significantly, he was beaten 9 times that year, even with an ERA like that. His final record was 22-9. Marichal had his best record at 26-9 with a 2.36 ERA. Don Drysdale, Koufax’s old partner on the Dodger staff, set a record by throwing 58 consecutive scoreless innings. He had a 2.15 ERA but only a 14-12 record. In the American league Luis Tiant of the Indians led with a 1.60 ERA, 264 strikeouts and 9 shut-outs but went only 21-9. His teammate, “Sudden” Sam McDowell, was second in ERA at 1.81 and had even more strike-outs, (283) but only a 15-14 record. But the star of the American league was Denny McLain, who became the first pitcher since Dizzy Dean in 1934 to win 30 games,. Denny was 31-6 and nobody’s done it since. He had a 1.96 ERA and 280 strike-outs.

The World Series that year featured two direct confrontations between Gibson and McLain: a 1.12 ERA vs. 31 wins! Gibson won both of them, shutting out the Tigers 4-0 in the opener with a series record 17 strikes outs and then winning a 10-1 laugher in Game 4. Mayo Smith opted to pitch McLain in game 6 and he won that one, 13-1 over Ray Washburn. Then the Tiger’s second best pitcher, Mickey Lolich beat Gibson, 4-1 in the final.

To baseball purists it was a trilling season. But to the General public it was a bore, full of 1-0 and 2-1 games. It may be that football, which tended to look better on television in those primitive days, was primed to take over as the #1 American sport anyway but Frick’s over reaction to Roger Maris breaking his buddy Babe Ruth’s record had pulled his sports pants down at exactly the wrong time.

Frick had retired in 1965. The owners decided they’d like to have a prominent military man become their new commissioners. Kenesaw Landis had been a judge, Happy Chandler a Governor and Frick and sportswriter. Now they wanted a General or an Admiral, just like Ike. They asked the Pentagon for the name of retiring officer who had a distinguished service record and was a baseball fan to see if he might want the job. At first it was offered to General Curtis LeMay but he turned it down, instead suggesting General William D. Eckert.

A possibly apocryphal story I’ve heard is that there were two Generals by that name and that the invitation was delivered to the wrong one, a desk jockey who knew nothing about baseball. Eckert’s subsequent career seems to suggest that that may be true. He had won the distinguished flying cross during World War II but had spent years in various desk jobs and knew little about the game, having not attended a baseball game in ten years. Supposedly the owners, when informed of the mistake, didn’t feel that they could publically withdraw the invitation so they could only hope this other General Eckert would turn it down. He didn’t.

Per SI: “Eckert kept notes on index cards. In his first public meeting, Eckert reached into his pocket and produced some index cards on which he had written a few reminders. Unfortunately, he welcomed the baseball writers and managers by reading from the wrong set of notes. He thanked them for helping the airline industry so much and spoke of technological advances being made in aviation. Managers looked at writers and writers at managers, until finally Lee MacPhail figured out what had gone wrong and went to the commissioner's aid. General Eckert was scheduled to give a speech that evening at a United Airlines cocktail party. It was not a brilliant beginning. “

The owners appointed McPhail to be the Commissioner’s assistant and he guided the neophyte through a four year term. The media game Eckert the nickname “The Unknown Soldier”. Per Baseball fever.com: “Eckert tried hard to succeed. He made a goal of visiting every team, never refusing an invite. The players seemed to like him as much as the owners seemed to have buyer’s remorse.” To them, he was a ‘perennial disappointment’.

It was not an era to have a weak commissioner. Not only was the popularity of the game slipping and it’s positon in American sports being challenged but the players union had hired Marvin Miller to organize and represent their interests. Eckert compounded things by refusing to cancel games after the Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy assassinations, “putting baseball in a bad light”.

The owners got smart and informed Eckert he would not be returning. His replacement was to be Bowie Kuhn, a lawyer who had represented the owners for 20 years. He thoroughly knew baseball, especially on the administrative end. He was also no stranger to labor negotiations. And he recognized that if baseball was to compete in the modern sports market, it needed to put runs on the scoreboard. He reversed Frick’s decisions on the strike zone and the height of the mound and baseball numbers went back to where they had been at the beginning of the decade.

Maris’ record lasted longer than Ruth’s did.

The 1960’s have been described as the “Second Dead Ball Era” because of the low scoring. But it wasn’t caused by a deadened ball. It was caused by an enlarged strike zone and a raised mound, both changes made at the insistence of Commissioner Ford Frick, who was afraid that expansion, (both of teams and the length of the season), would result in “phony” record breaking. Instead, it plunged baseball into an era of anemic offense, just at the time when pro football was beginning to get a mass audience and challenge baseball’s status as the “national past-time”. It was really the Ford Frick Era.

As I mentioned in my last article, Bill James did an extensive study of what Willie Davis’ numbers actually were over the course of his career and what his numbers would have bene in a statistically average year. Let’s look at his numbers in the 1960’s, (full seasons only), both the actual numbers and the “James numbers”:

1961 Actual: .254BA .451SP 192BP 89RP James: .256BA .453SP 193BP 89RP

1962 Actual: .285BA .453SP 346BP 167RP James: .299BA .474SP 369BP 189RP

1963 Actual: .245BA .365SP 238BP 111RP James: .266BA .396SP 266BP 136RP

1964 Actual: .294BA .413SP 317BP 156RP James: .323BA .455SP 364BP 198RP

1965 Actual: .238BA .346SP 232BP 99RP James: .265BA .386SP 269BP 126RP

1966 Actual: .284BA .405SP 289BP 124RP James: .306BA .438SP 322BP 150RP

1967 Actual: .257BA .367SP 258BP 100RP James: .293BA .418SP 316BP 138RP

1968 Actual: .250BA .351SP 293BP 110RP James: .298BA .376SP 343BP 167RP

1969 Actual: .311BA .456SP 284BP 114RP James: .329BA .483SP 309BP 130RP

(BP and RP are my numbers: runs and bases produced, based on the actual and James numbers)

James: “The essential point I am making is this: Willie Davis, throughout the 1960’s was regarded as a huge disappointment, a player who never played up to his perceived ability…The is completely unfair. Willie Davis was a terrific player. True, he didn’t walk and he was a not particularly consistent but his good years, in context, are quite impressive. The Dodgers won the pennant in 1963, 1965 and 1966 and one of the key reasons they did was because they had Willie Davis. He should not be regarded as a failure, merely because he had to play his prime seasons in such difficult hitting conditions.”

James does something similar with other players who hit the big leagues in the 60’s, although not in as much detail. He talks about Pete Ward, who it .282 with 23 homer runs and 94RBI in 1964. In a normal context, that would be .298-25-107. In the 1990’s he would have hit .332 with 29 homers and 137 RBI. Tom Tresh “in 1968 hit .233- yet he was as valuable in that season as Ed Delahanty was in 1894, when Delahanty hit .407 or as Joe Medwick was in 1938, when Medwick hit .322 with 21 homers, 122 RBI or as Albert Belle was in 1996 when Belle hit .274 with 45 doubles, 30 homers and 116 RBI.” In his article on Vada Pinson he says: The pitchers took control of the game in 1963, cutting into everybody’s numbers and making ‘perennial disappointments’ of many of the young players of that era, including Willie Davis, Frank Howard, Tom Tresh and Norm Cash.”

All kinds of such comparisons like that can be made. The point is, the players of the 60’s are as under-evaluated due to their numbers as the players of the 90’s tend to be over-evaluated due to their numbers.

One of my favorite comparisons is between the American League, which hit a cumulative .230, to the National League of 1930 that hit .303. The 1930 National League Batting champion was Bill Terry, who hit .401, the last National League .400 hitter. In 1968 Carl Yastremski won the American League with a batting average 100 points less than that, .301. Was Yaz really 100 points worse than Terry? I think we can assume that if HIS league had hit .303 instead of .230, Yaz would probably have hit something like .374 and that if Terry’s league had hit .230, Terry would have hit more like .328. Terry was still better but by 27 points, not 100.

Of course, the pitchers had a golden era. In fact, they were the real stars of the era. Sandy Koufax was probably the most admired player in the game in the mdi 60’s. From 1962-66 he won 111 games, lost 34, struck out 1,444 batters, allowed 1275 baserunners and 298 earned runs in 1377 innings, giving him a “WHIP” of 0.926 and an ERA 1.95- for FIVE years! He also pitched 4 no-hitters, one of which was a perfect game. An even bigger sign of the times was that he completed 100 out of 314 starts- nearly 1/3 and threw 33 shut-outs. He retired at age 31 because of an arm problem that I’ve read could easily have been fixed today.

His great rival for much of the decade was San Francisco’s Juan Marichal, who won over 20 games six times and over 25 games three of those times. After Koufax retired and the Giants faded, the big name was Bob Gibson of the Cardinals, who won over 20 games five times for a team that won three pennant and two World Series. Marichal in his career went 243-142, Gibson 251-174, yet it is Gibson who is best remembered today, probably because the Giants kept finishing second to the Dodgers and Cardinals, winning the pennant only in 1962, a year when Marichal, just beginning to establish himself, went only 18-11 and the Giant s lost the series.

1968 was a pitcher’s paradise Gibson set a record for the lowest ever ERA, (depending on your limit for innings), of 1.12. He had 13 shut-outs. Significantly, he was beaten 9 times that year, even with an ERA like that. His final record was 22-9. Marichal had his best record at 26-9 with a 2.36 ERA. Don Drysdale, Koufax’s old partner on the Dodger staff, set a record by throwing 58 consecutive scoreless innings. He had a 2.15 ERA but only a 14-12 record. In the American league Luis Tiant of the Indians led with a 1.60 ERA, 264 strikeouts and 9 shut-outs but went only 21-9. His teammate, “Sudden” Sam McDowell, was second in ERA at 1.81 and had even more strike-outs, (283) but only a 15-14 record. But the star of the American league was Denny McLain, who became the first pitcher since Dizzy Dean in 1934 to win 30 games,. Denny was 31-6 and nobody’s done it since. He had a 1.96 ERA and 280 strike-outs.

The World Series that year featured two direct confrontations between Gibson and McLain: a 1.12 ERA vs. 31 wins! Gibson won both of them, shutting out the Tigers 4-0 in the opener with a series record 17 strikes outs and then winning a 10-1 laugher in Game 4. Mayo Smith opted to pitch McLain in game 6 and he won that one, 13-1 over Ray Washburn. Then the Tiger’s second best pitcher, Mickey Lolich beat Gibson, 4-1 in the final.

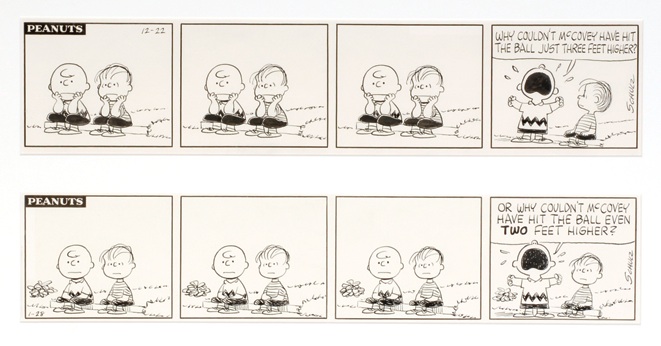

To baseball purists it was a trilling season. But to the General public it was a bore, full of 1-0 and 2-1 games. It may be that football, which tended to look better on television in those primitive days, was primed to take over as the #1 American sport anyway but Frick’s over reaction to Roger Maris breaking his buddy Babe Ruth’s record had pulled his sports pants down at exactly the wrong time.

Frick had retired in 1965. The owners decided they’d like to have a prominent military man become their new commissioners. Kenesaw Landis had been a judge, Happy Chandler a Governor and Frick and sportswriter. Now they wanted a General or an Admiral, just like Ike. They asked the Pentagon for the name of retiring officer who had a distinguished service record and was a baseball fan to see if he might want the job. At first it was offered to General Curtis LeMay but he turned it down, instead suggesting General William D. Eckert.

A possibly apocryphal story I’ve heard is that there were two Generals by that name and that the invitation was delivered to the wrong one, a desk jockey who knew nothing about baseball. Eckert’s subsequent career seems to suggest that that may be true. He had won the distinguished flying cross during World War II but had spent years in various desk jobs and knew little about the game, having not attended a baseball game in ten years. Supposedly the owners, when informed of the mistake, didn’t feel that they could publically withdraw the invitation so they could only hope this other General Eckert would turn it down. He didn’t.

Per SI: “Eckert kept notes on index cards. In his first public meeting, Eckert reached into his pocket and produced some index cards on which he had written a few reminders. Unfortunately, he welcomed the baseball writers and managers by reading from the wrong set of notes. He thanked them for helping the airline industry so much and spoke of technological advances being made in aviation. Managers looked at writers and writers at managers, until finally Lee MacPhail figured out what had gone wrong and went to the commissioner's aid. General Eckert was scheduled to give a speech that evening at a United Airlines cocktail party. It was not a brilliant beginning. “

The owners appointed McPhail to be the Commissioner’s assistant and he guided the neophyte through a four year term. The media game Eckert the nickname “The Unknown Soldier”. Per Baseball fever.com: “Eckert tried hard to succeed. He made a goal of visiting every team, never refusing an invite. The players seemed to like him as much as the owners seemed to have buyer’s remorse.” To them, he was a ‘perennial disappointment’.

It was not an era to have a weak commissioner. Not only was the popularity of the game slipping and it’s positon in American sports being challenged but the players union had hired Marvin Miller to organize and represent their interests. Eckert compounded things by refusing to cancel games after the Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy assassinations, “putting baseball in a bad light”.

The owners got smart and informed Eckert he would not be returning. His replacement was to be Bowie Kuhn, a lawyer who had represented the owners for 20 years. He thoroughly knew baseball, especially on the administrative end. He was also no stranger to labor negotiations. And he recognized that if baseball was to compete in the modern sports market, it needed to put runs on the scoreboard. He reversed Frick’s decisions on the strike zone and the height of the mound and baseball numbers went back to where they had been at the beginning of the decade.

Maris’ record lasted longer than Ruth’s did.