SWC75

Bored Historian

- Joined

- Aug 26, 2011

- Messages

- 32,450

- Like

- 62,607

(I'm taking this time to review all the stuff that has collected on my computer over the years, including the WORD documents I have created on various subjects. If something looks like ti would still be interesting, i'll post it to this board to give us something to think and talk about other than viruses or poli-ticks.)

The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs

en.wikipedia.org

en.wikipedia.org

(You can get it through the Amazon link, above.)

A Lifelong Study

I’ve come back from vacationing in our 50th state having completed reading Bill Jenkinson’s remarkable book on Babe Ruth, “The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs”. I posted on this a couple of weeks back, having skimmed it and I assumed that he meant some year where the Babe, in spring training, exhibition games, regular season games, posts season games and barnstorming between seasons had hit that many home runs. That’s not what he meant.

Jenkinson has made a career studying the career of Babe Ruth. He started out as a Dick Allen fan, trying to prove that Allen hit the longest homers that had ever been hit. At the end he was still impressed with Allen but had become convinced that nobody- in his time or any later time, ever hit baseballs the way Babe Ruth hit them.

In a 28 year study, Jenkinson has actually charted every home run Babe Ruth ever hit in the big leagues. In an appendix, he lists the approximate distance of each one. He thinks he’s within 10 feet of being correct on each one, either way. This may seem unlikely considering the games were played as long as 90 years ago. But big cities had many newspapers in those days. New York City had 18 of them. Other big league towns had from 3-6. The games were covered in elaborate detail, the way a major college football game might be dissected in the local paper today. There would be pictures of the ballpark with diagrams of where home runs were hit and detailed descriptions of all the major plays. Using these sources along with computer simulations of ball parks and modern rules for determining the “distance” of home runs that were interrupted by grandstands and walls and thus prevented from reaching the ground, Jenkinson thinks he’s got a pretty accurate map of Ruth’s career. He’s even been able to estimate where many drives landed on the field that would have been home runs in modern stadiums, although there were many drives that might have gone 390-410 feet but were considered unremarkable in ballparks where the fences often reached 450-500 feet from home plate.

Ballparks

And that’s Jenkinson’s biggest single point: that ballparks used to be much bigger than they are now. There was some variance but here are the outfield fences in each big-league ballpark at their maximum during the years Babe Ruth played:

Fenway Park (Boston) 324 to the left field corner; 379 to left center, 488 to deepest center field, 370 to right center and 359 to the right field corner.

Braves Field (Boston) 301-460-490-429-296

Yankee Stadium (New York) 301-460-490-429-296

Polo Grounds (New York) 287-447-505-440-257

Ebbets Field (New York) 419-365-466-352-301

Schibe Park (Philadelphia) 380-405-502-400-393

Baker Bowl (Philadelphia) 342-320-408-300-281

Griffith Stadium (Washington) 424-383-421-378-328

Forbes Field (Pittsburgh) 369-406-435-408-376

League Park (Cleveland) 385-415-505-400-290

Municipal Stadium (Cleveland) 322-463-470-463-322

Crosley Field (Cincinnati) 360-380-420-383-400

Navin Field, (aka Briggs Stadium- later Tiger Stadium in Detroit) 345-365-467-370-370

Comiskey Park (Chicago) 365-382-455-382-365

Wrigley Field (Chicago) 364-357-447-363-321

Sportsman’s Park (St. Louis) 360-379-450-354-325

The distances of current big-league ballparks are readily available on the net. Jenkinson sums it up by saying that the average distance to outfield walls in Babe Ruth’s time was 28 feet farther than modern ballparks. Also the height of outfield walls was between 10 and 40 feet. To Jenkinson, the gradual reduction in the size of ballparks is the equivalent of the basket getting lower and lower in basketball or the field shorter and shorter in football. He doesn’t use the term but what we have now is basically arena baseball. If LeBron James were dunking on an 8 foot basket would he be regarded as the equal of Wilt Chamberlain? If LeDainian Tomlinson were playing on an 80 yard field, would he be compared to Jim Brown? But Barry Bonds, playing in smaller ballparks, (with a juiced ball and steroids), is favorably compared, (by some) to Babe Ruth.

Of course, some of those ballparks had cozy corners. The Polo Grounds, where the Yankees played until 1922, was an absurd 287 down the left field line and 257 down the right field line. Yankee Stadium was 301/296. Modern ballparks tend to go 330 down the line, (and 375 to power alleys and 410 to center, if that). So the Babe could get some cheap home runs, too. But the greatest power hitters are spray hitters, not pull hitters. They find they don’t have to pull the ball to get it out. Babe Ruth hit 347 home runs at home, 367 on the road. The “spray charts” in Jenkinson’s book do show that Ruth tried to pull the ball more at home. But, by my count, only 23 of his 714 home runs traveled less than 330 feet. The average length of his 714 career home runs was 416 feet. In his greatest year, 1921, it was 434 feet. His 713th career home run went 500 feet. #714 went 540 feet. His longest home run and the longest home run ever hit in a big league game was at Navin Field on July 18, 1921. It went directly out over center field fence and landed across an intersection, at least 575 feet from home plate. One contemporary estimate was 601 feet but Jenkinson doesn’t think it went quite that far: he’s never found any documented 600 foot home run, even in exhibitions, although he thinks there may have been one during a batting exhibition at Wilkes Barre Pa on 10/12/26, by the Babe, of course. The ball went over the left center field fence, past a road and landed, according to an old man Jenkinson interviewed who was a 10 year old kid at the time, in left field- of a ball field across the road, possibly 650 feet away.

Pure Power

One thing that was remarkable about Ruth was his opposite field power. He it the only documented 500 foot opposite field home run, which landed on a garage roof over the left center field fence at Fenway on 7/23/28. It went 515 feet. Jenkinson, in fact feels that Babe’s greatest power was shown from left center to straightaway center, which he calls “Bambino Alley”. He had at least a dozen balls that were hit within 5 degrees of deepest center field that went at least 475 feet.

Overall, the Babe hit 198 homers that went at least 450 feet and 45 that went at least 500 feet, (three more on the World Series). Barry Bonds has never hit a 500 foot home run in an official game. He had three 450 foot homers prior to the 2000 and 33 since. Mark McGwire’s longest home run prior to 1995 was 455 feet. After that he had a dozen 500 footers and wound up with seventy-four 450 footers. Mickey Mantle’s most famous home run was his 1953 shot in Griffith Stadium in Washington that allegedly went 565 feet. Actually, that’s where a kid was found holding the ball. Jenkinson believes that the ball actually landed about 510 feet from home plate, a tremendous shot and the only one ever to leave the park over the left field fence in that stadium. But 510 is a distance Ruth exceeded 15 times. Mickey said he hit the ball harder than the one in Washington “five or six times”. The two most famous were the ones hit off the façade at the top of the right field grandstand at Yankee Stadium in 1956 and 1963. There was no façade in the Babe’s day: there was no roof. The façade would correspond to about the tenth row at the top of the grandstand and the Babe, according to Jenkinson, hit at least 8 balls above that line in his time there. Reggie Jackson’s famous home run off the light tower in Detroit in 1971, (the inspiration for Roy Hobbs’ home run at the end of “The Natural”), would have gone about 520 feet. The Babe exceeded that 8 times. When the author told Reggie where Babe had hit his longest home run in Fenway Park, Reggie was “flabbergasted”. On April 18, 1919, the Red Sox played an exhibition game in Babe’s home town vs. the Baltimore Orioles, who that season would win the first of 7 straight International League pennants as a fully independent team full of future major leaguers. The Babe hit four home runs in that game, which according to a diagram on a photo from the local paper, went 580 feet, 450 feet, 500 feet and 550 feet.

What he would do today

Jenkinson got the title of his book from analyzing Babe’s 1921 season, generally considered to be the greatest season ever- by anybody. The Babe hit 59 actual home runs. Of those, he estimates 5, (4 in Yankee Stadium, 1 in Cleveland) that were hit right down the line would not have gone out in an average big-league stadium of our time. There were three rules in those days that no longer exist that affected home run totals. One is that what we now call a ground-rule double- a ball that hits in the field and bounces over the fence- was called a home run then. Jenkinson found no account of the Babe getting credit for a home run by that means in his entire career, (remember that the fences ranged from 10-40 feet high and up to 500 feet away- and the field was grass). A second is that a walk-off home run only counted as a home run if the homer itself was the winning run. Otherwise, the game ended when the winning run was scored and the batter got credit for however many bases he’d taken at that point. Jenkinson figures Ruth lost 4 home runs in his career that way, none in 1921. A third was the “fair/foul rule”, which had umpires judging whether a drive that went over the fence was fair our foul by where it actually landed, or was last seen, (a judgment they had to make several times with Ruth). Jenkinson feels the Babe lost at least 50 home runs in his career before this rule was changed in 1931, at least 4 in 1921.(An appendix lists 67 suspected “fair-foul home runs, including 10 in 1921, but the author is being conservative.) The Babe also hit 10 drives off the distant fences that went far enough to be home runs now. Jenkinson figures at least a couple of them would have gone over the shorter fences we have now. Then there are the drives that fell into the spacious outfields of 1921 and produced doubles, triples and outs but would have been over any modern day fence. Jenkinson believes there were at least 40 of them. Then, by multiplying by 162/154, he comes up with the amazing statistic of his title: He believes that the Babe Ruth of 1921 would have hit at least 104 home runs if he’d played all his games in an average modern ballpark. And that’s a conservative estimate.

He made the same analysis of every season of Ruth’s career and thinks the 1927 Babe Ruth would have hit 91 home runs, the 1920 Babe would have had 86, the 1924, 1926, 1928, 1929 and 1930 Babes would have all had over 70 and the 1919, 1922, 1923 and 1931 Babes would have reached the 60 mark. He estimates that Babe Ruth would have hit 1,158 regular season home runs and 23 more in the World Series. He also looked at Barry Bond’s last really good year, (2004), when he hit 45 home runs and decided that 27 of Barry’s homers would have been out in the Babe’s time. I don’t know why he didn’t do Bond’s greatest year, 2001, when he hit 73 home runs. But since 27 is exactly 60% of 45, I assume the Barry Bonds of 2001 would have had about 44 home runs in Babe’s

time.

Comparisons

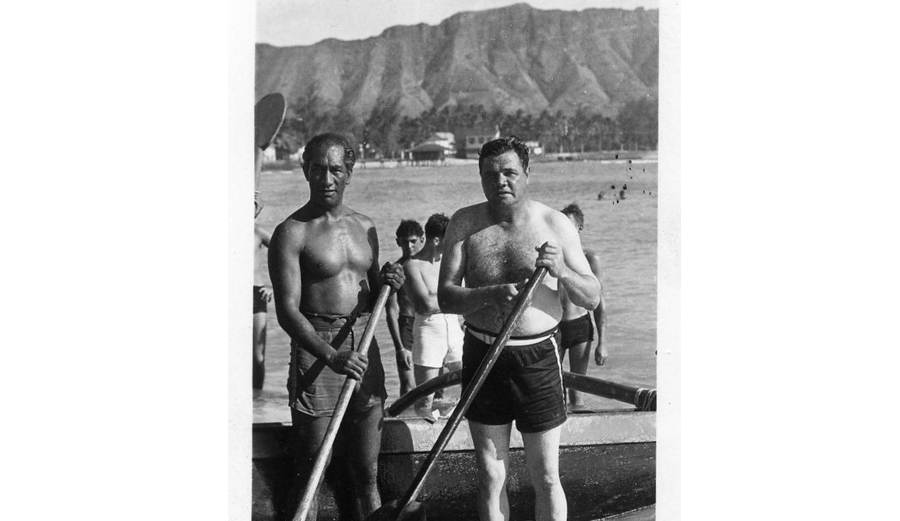

Jenkinson goes on at length comparing the eras in other ways, such as the fact that they didn’t believe in “wasting your legs” in physical training at that time and the Babe never had much muscle definition. I saw a picture of him in Hawaii posing on the beach with Duke Kahanamoku. He wasn’t really fat but was sort of chunky looking.

I have a book by Robert Creamer with pictures of Ruth working out after his fabulous 1921 season and he actually looks kind of skinny, especially in the arms. Jenkinson has Babe’s official weight for the start of spring training for several different seasons: He was about 6-2 ½ and weighed 185 pounds in 1914, 195 in 1915, 217 in 1922, 205 in 1923, 230 in 1924, 250 in 1925, (the year of his “bellyache”), 226 in 1926, 223 in 1927, 224 in 1928, 230 in 1929 and 1930, 228 in 1931 and 235 in 1934. He was never “ripped” but he was never really fat, either. John Goodman is a heck of an actor but he must have been at least 100 pound heavier than any of these weights when he played Ruth in that movie.

One of the complaints about Ruth is that he “never played against black players”. The opposite is true. The Babe would barnstorm against anybody, even defying the Ku Klux Klan to play the Kansas City Monarchs in 1922. He was also defying Judge Landis, the bigoted Commissioner, who suspended him for “barnstorming”, which everyone did in those days, but really for playing against blacks. Black players relished the chance to play white major leaguers in exhibitions and gave it all they had to beat them to prove that they should be in the big leagues. They won 2/3 such games over the years. Ruth batted 55 times in games against Negro League teams, had 25 hits, (.455) and 12 home runs, one of which left Satchel Paige “speechless”, according to Buck O’Neill. Ruth was good friends with early black superstar John Henry Lloyd and, according to Negro League Hall of Famer Judy Johnson, was “his hero”.

It was the belief in those days that the key to long distance hitting in those days was a big bat. In 1921 Babe swung a 54 once bat. These days, most sluggers use 32 or 33 ounce bats. A 54 ounce bat when swung as swiftly as a 32 ounce bat will send the ball farther but they normally can’t be swung that fast so modern players go with the smaller bats. Ruth by 1927 settled for a 44 ounce bat but that’s about as low as it got. Doctoring the ball was banned early in Ruth’s career, (1920 as a health measure in the wake of the influenza epidemic) but umpires in practice often failed to enforce it and pitchers already in the league using spitters were “grandfathered” in, allowing them to continue to do so for the rest of their careers. As late as the 1970s, balls were left in play unless players requested they be replaced. As Jenkinson puts it, “If Alex Rodriquez looked at the balls thrown at Mike Schmidt, he’d be surprised. If Mike Schmidt looked at the balls Ted Williams played with, he’d be dismayed. If Ted Williams looked at the balls Babe Ruth had to hit, he would have been horrified.” Then there’s the issue of the armour a modern hitter like Barry Bonds wears so he can crowd the plate and not fear getting hit by a pitch. The Babe had no such advantage, (not even the muscular build-up). And he’d been on the field when Ray Chapman got killed by a pitch in 1920.

Another big point Jenkinson makes is the disappearance of the high strike in baseball. In Ruth’s time, the strike zone was called pretty much as the rules describe: from the letter to the knees. Now anything above the waist is “high”. Ted Williams once had trouble with a pitcher named Ellis Kinder. He finally got his first home run off him. He attributed it to the fact that Kinder had finally made the mistake of getting the ball down instead of “chest-level”. Ted said he “could not hit a ball squarely” if it were at chest level. But a chest level ball in those days was a strike. Now it’s a ball.

All-Around Player

Jenkinson also talks about how much of an underrated all-around player Ruth was. He read many accounts of great defensive plays Ruth made in the outfield and came across a quote by Tris Speaker calling Ruth “One of the greatest defensive outfielders I have ever seen.” The Babe was also an aggressive baserunner, stealing as many as 17 bases in a season and 123 in his career. He had ten career steals of home, seven inside the park home runs and 136 triples. The old films clips always show him trotting around the bases after a home run but he could really run. There are numerous accounts of his playing hurt or seriously ill. He virtually always played, knowing the fans came to see him. And the Yankees took advantage of that, scheduling exhibitions on every off day and on their trips north from spring training. With that and his barnstorming, the Babe played over 200 games a year. And, of course, he was a great pitcher who could have won 300 games if he’d kept at it.

Conclusions

The conclusion seems inescapable that Babe Ruth would be much greater today than he was in his own time, even as incomparable. Players that appear to have achieved as much or more are clearly not in his class at all. And he didn’t do it by using drugs to turn himself into a cartoon action figure. Doctors in his time tried to determine how he did do it. They determined that he had “abnormally thick wrists and forearms, high coordination, superior eyesight, hearing and ‘nerves’, (reactions), and a high degree of ‘perceptual intelligence’”. His chest when expanded was 7 inches wider than normal. The average is 2 inches. That’s supposed to be a sign of natural strength. I would use another term popular to modern commentators. I think the game just “slowed down” for the Babe due to his “perceptual intelligence” and he was thus able to do things other people could not do.

He was so superior to everyone in his own time that is was almost superfluous to study his accomplishments. He was Babe Ruth and nobody else was. His abilities and achievements never had to be carefully studied to marshal a defense against some challenger to his reputation. Instead his colorful, almost clownish personality was what people reacted to the most. That image was left with us and when other players under more favorable conditions matched or exceeded his records and it came to assumed that he was just a creature of his time, Grandpa’s hero, and had been caught and passed by the march of time. Bill Jenkinson has set the record straight, subtitling his book “The Recrowning of Baseball’s Greatest Slugger”.

(I used Jenkinson’s book, which is 412 pages long and discusses these things in much more detail while also including many personal anecdotes about the Babe’s life and personality. I highly recommended it be read in its entirety. Some of the numbers are my computations based on Jenkinson’s numbers. I also used other books Like “Green Cathedrals” and “Total Baseball” for some of the information.)

Nicknames

By the way, the Babe surely leads everyone in nicknames, as writers sought greater and greater hyperbole to describe this phenom. They included: The Ace of Clubbers, The Baltimore Adonis, The Bambino, The Behemoth of Bust, The Boston Mauler, The Caliph of Clout, The Goliath of the Bludgeon, The Grand Colossus of Hitters, The Heroic Figure of our National Sport, (has anybody called Barry that?), The Human Howitzer, The Jumbo Jouster, The Khedive of Klout, The Maharajah of Mash, The Mighty Man of Baseball, The Monarch of Maulers, The Potentate of Pounders, Ruthless Ruth, The Sultan of Swat, (my favorite), The Terror of Pitchers, The Titan of Thump, what Wali of Wallop, the Wazier of Wham, The Wizard of Wallop, The Emporer, Hercules, Samson, Superman, Tarzan and Zeus, among many others.

The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs

The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs - Wikipedia

(You can get it through the Amazon link, above.)

A Lifelong Study

I’ve come back from vacationing in our 50th state having completed reading Bill Jenkinson’s remarkable book on Babe Ruth, “The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs”. I posted on this a couple of weeks back, having skimmed it and I assumed that he meant some year where the Babe, in spring training, exhibition games, regular season games, posts season games and barnstorming between seasons had hit that many home runs. That’s not what he meant.

Jenkinson has made a career studying the career of Babe Ruth. He started out as a Dick Allen fan, trying to prove that Allen hit the longest homers that had ever been hit. At the end he was still impressed with Allen but had become convinced that nobody- in his time or any later time, ever hit baseballs the way Babe Ruth hit them.

In a 28 year study, Jenkinson has actually charted every home run Babe Ruth ever hit in the big leagues. In an appendix, he lists the approximate distance of each one. He thinks he’s within 10 feet of being correct on each one, either way. This may seem unlikely considering the games were played as long as 90 years ago. But big cities had many newspapers in those days. New York City had 18 of them. Other big league towns had from 3-6. The games were covered in elaborate detail, the way a major college football game might be dissected in the local paper today. There would be pictures of the ballpark with diagrams of where home runs were hit and detailed descriptions of all the major plays. Using these sources along with computer simulations of ball parks and modern rules for determining the “distance” of home runs that were interrupted by grandstands and walls and thus prevented from reaching the ground, Jenkinson thinks he’s got a pretty accurate map of Ruth’s career. He’s even been able to estimate where many drives landed on the field that would have been home runs in modern stadiums, although there were many drives that might have gone 390-410 feet but were considered unremarkable in ballparks where the fences often reached 450-500 feet from home plate.

Ballparks

And that’s Jenkinson’s biggest single point: that ballparks used to be much bigger than they are now. There was some variance but here are the outfield fences in each big-league ballpark at their maximum during the years Babe Ruth played:

Fenway Park (Boston) 324 to the left field corner; 379 to left center, 488 to deepest center field, 370 to right center and 359 to the right field corner.

Braves Field (Boston) 301-460-490-429-296

Yankee Stadium (New York) 301-460-490-429-296

Polo Grounds (New York) 287-447-505-440-257

Ebbets Field (New York) 419-365-466-352-301

Schibe Park (Philadelphia) 380-405-502-400-393

Baker Bowl (Philadelphia) 342-320-408-300-281

Griffith Stadium (Washington) 424-383-421-378-328

Forbes Field (Pittsburgh) 369-406-435-408-376

League Park (Cleveland) 385-415-505-400-290

Municipal Stadium (Cleveland) 322-463-470-463-322

Crosley Field (Cincinnati) 360-380-420-383-400

Navin Field, (aka Briggs Stadium- later Tiger Stadium in Detroit) 345-365-467-370-370

Comiskey Park (Chicago) 365-382-455-382-365

Wrigley Field (Chicago) 364-357-447-363-321

Sportsman’s Park (St. Louis) 360-379-450-354-325

The distances of current big-league ballparks are readily available on the net. Jenkinson sums it up by saying that the average distance to outfield walls in Babe Ruth’s time was 28 feet farther than modern ballparks. Also the height of outfield walls was between 10 and 40 feet. To Jenkinson, the gradual reduction in the size of ballparks is the equivalent of the basket getting lower and lower in basketball or the field shorter and shorter in football. He doesn’t use the term but what we have now is basically arena baseball. If LeBron James were dunking on an 8 foot basket would he be regarded as the equal of Wilt Chamberlain? If LeDainian Tomlinson were playing on an 80 yard field, would he be compared to Jim Brown? But Barry Bonds, playing in smaller ballparks, (with a juiced ball and steroids), is favorably compared, (by some) to Babe Ruth.

Of course, some of those ballparks had cozy corners. The Polo Grounds, where the Yankees played until 1922, was an absurd 287 down the left field line and 257 down the right field line. Yankee Stadium was 301/296. Modern ballparks tend to go 330 down the line, (and 375 to power alleys and 410 to center, if that). So the Babe could get some cheap home runs, too. But the greatest power hitters are spray hitters, not pull hitters. They find they don’t have to pull the ball to get it out. Babe Ruth hit 347 home runs at home, 367 on the road. The “spray charts” in Jenkinson’s book do show that Ruth tried to pull the ball more at home. But, by my count, only 23 of his 714 home runs traveled less than 330 feet. The average length of his 714 career home runs was 416 feet. In his greatest year, 1921, it was 434 feet. His 713th career home run went 500 feet. #714 went 540 feet. His longest home run and the longest home run ever hit in a big league game was at Navin Field on July 18, 1921. It went directly out over center field fence and landed across an intersection, at least 575 feet from home plate. One contemporary estimate was 601 feet but Jenkinson doesn’t think it went quite that far: he’s never found any documented 600 foot home run, even in exhibitions, although he thinks there may have been one during a batting exhibition at Wilkes Barre Pa on 10/12/26, by the Babe, of course. The ball went over the left center field fence, past a road and landed, according to an old man Jenkinson interviewed who was a 10 year old kid at the time, in left field- of a ball field across the road, possibly 650 feet away.

Pure Power

One thing that was remarkable about Ruth was his opposite field power. He it the only documented 500 foot opposite field home run, which landed on a garage roof over the left center field fence at Fenway on 7/23/28. It went 515 feet. Jenkinson, in fact feels that Babe’s greatest power was shown from left center to straightaway center, which he calls “Bambino Alley”. He had at least a dozen balls that were hit within 5 degrees of deepest center field that went at least 475 feet.

Overall, the Babe hit 198 homers that went at least 450 feet and 45 that went at least 500 feet, (three more on the World Series). Barry Bonds has never hit a 500 foot home run in an official game. He had three 450 foot homers prior to the 2000 and 33 since. Mark McGwire’s longest home run prior to 1995 was 455 feet. After that he had a dozen 500 footers and wound up with seventy-four 450 footers. Mickey Mantle’s most famous home run was his 1953 shot in Griffith Stadium in Washington that allegedly went 565 feet. Actually, that’s where a kid was found holding the ball. Jenkinson believes that the ball actually landed about 510 feet from home plate, a tremendous shot and the only one ever to leave the park over the left field fence in that stadium. But 510 is a distance Ruth exceeded 15 times. Mickey said he hit the ball harder than the one in Washington “five or six times”. The two most famous were the ones hit off the façade at the top of the right field grandstand at Yankee Stadium in 1956 and 1963. There was no façade in the Babe’s day: there was no roof. The façade would correspond to about the tenth row at the top of the grandstand and the Babe, according to Jenkinson, hit at least 8 balls above that line in his time there. Reggie Jackson’s famous home run off the light tower in Detroit in 1971, (the inspiration for Roy Hobbs’ home run at the end of “The Natural”), would have gone about 520 feet. The Babe exceeded that 8 times. When the author told Reggie where Babe had hit his longest home run in Fenway Park, Reggie was “flabbergasted”. On April 18, 1919, the Red Sox played an exhibition game in Babe’s home town vs. the Baltimore Orioles, who that season would win the first of 7 straight International League pennants as a fully independent team full of future major leaguers. The Babe hit four home runs in that game, which according to a diagram on a photo from the local paper, went 580 feet, 450 feet, 500 feet and 550 feet.

What he would do today

Jenkinson got the title of his book from analyzing Babe’s 1921 season, generally considered to be the greatest season ever- by anybody. The Babe hit 59 actual home runs. Of those, he estimates 5, (4 in Yankee Stadium, 1 in Cleveland) that were hit right down the line would not have gone out in an average big-league stadium of our time. There were three rules in those days that no longer exist that affected home run totals. One is that what we now call a ground-rule double- a ball that hits in the field and bounces over the fence- was called a home run then. Jenkinson found no account of the Babe getting credit for a home run by that means in his entire career, (remember that the fences ranged from 10-40 feet high and up to 500 feet away- and the field was grass). A second is that a walk-off home run only counted as a home run if the homer itself was the winning run. Otherwise, the game ended when the winning run was scored and the batter got credit for however many bases he’d taken at that point. Jenkinson figures Ruth lost 4 home runs in his career that way, none in 1921. A third was the “fair/foul rule”, which had umpires judging whether a drive that went over the fence was fair our foul by where it actually landed, or was last seen, (a judgment they had to make several times with Ruth). Jenkinson feels the Babe lost at least 50 home runs in his career before this rule was changed in 1931, at least 4 in 1921.(An appendix lists 67 suspected “fair-foul home runs, including 10 in 1921, but the author is being conservative.) The Babe also hit 10 drives off the distant fences that went far enough to be home runs now. Jenkinson figures at least a couple of them would have gone over the shorter fences we have now. Then there are the drives that fell into the spacious outfields of 1921 and produced doubles, triples and outs but would have been over any modern day fence. Jenkinson believes there were at least 40 of them. Then, by multiplying by 162/154, he comes up with the amazing statistic of his title: He believes that the Babe Ruth of 1921 would have hit at least 104 home runs if he’d played all his games in an average modern ballpark. And that’s a conservative estimate.

He made the same analysis of every season of Ruth’s career and thinks the 1927 Babe Ruth would have hit 91 home runs, the 1920 Babe would have had 86, the 1924, 1926, 1928, 1929 and 1930 Babes would have all had over 70 and the 1919, 1922, 1923 and 1931 Babes would have reached the 60 mark. He estimates that Babe Ruth would have hit 1,158 regular season home runs and 23 more in the World Series. He also looked at Barry Bond’s last really good year, (2004), when he hit 45 home runs and decided that 27 of Barry’s homers would have been out in the Babe’s time. I don’t know why he didn’t do Bond’s greatest year, 2001, when he hit 73 home runs. But since 27 is exactly 60% of 45, I assume the Barry Bonds of 2001 would have had about 44 home runs in Babe’s

time.

Comparisons

Jenkinson goes on at length comparing the eras in other ways, such as the fact that they didn’t believe in “wasting your legs” in physical training at that time and the Babe never had much muscle definition. I saw a picture of him in Hawaii posing on the beach with Duke Kahanamoku. He wasn’t really fat but was sort of chunky looking.

I have a book by Robert Creamer with pictures of Ruth working out after his fabulous 1921 season and he actually looks kind of skinny, especially in the arms. Jenkinson has Babe’s official weight for the start of spring training for several different seasons: He was about 6-2 ½ and weighed 185 pounds in 1914, 195 in 1915, 217 in 1922, 205 in 1923, 230 in 1924, 250 in 1925, (the year of his “bellyache”), 226 in 1926, 223 in 1927, 224 in 1928, 230 in 1929 and 1930, 228 in 1931 and 235 in 1934. He was never “ripped” but he was never really fat, either. John Goodman is a heck of an actor but he must have been at least 100 pound heavier than any of these weights when he played Ruth in that movie.

One of the complaints about Ruth is that he “never played against black players”. The opposite is true. The Babe would barnstorm against anybody, even defying the Ku Klux Klan to play the Kansas City Monarchs in 1922. He was also defying Judge Landis, the bigoted Commissioner, who suspended him for “barnstorming”, which everyone did in those days, but really for playing against blacks. Black players relished the chance to play white major leaguers in exhibitions and gave it all they had to beat them to prove that they should be in the big leagues. They won 2/3 such games over the years. Ruth batted 55 times in games against Negro League teams, had 25 hits, (.455) and 12 home runs, one of which left Satchel Paige “speechless”, according to Buck O’Neill. Ruth was good friends with early black superstar John Henry Lloyd and, according to Negro League Hall of Famer Judy Johnson, was “his hero”.

It was the belief in those days that the key to long distance hitting in those days was a big bat. In 1921 Babe swung a 54 once bat. These days, most sluggers use 32 or 33 ounce bats. A 54 ounce bat when swung as swiftly as a 32 ounce bat will send the ball farther but they normally can’t be swung that fast so modern players go with the smaller bats. Ruth by 1927 settled for a 44 ounce bat but that’s about as low as it got. Doctoring the ball was banned early in Ruth’s career, (1920 as a health measure in the wake of the influenza epidemic) but umpires in practice often failed to enforce it and pitchers already in the league using spitters were “grandfathered” in, allowing them to continue to do so for the rest of their careers. As late as the 1970s, balls were left in play unless players requested they be replaced. As Jenkinson puts it, “If Alex Rodriquez looked at the balls thrown at Mike Schmidt, he’d be surprised. If Mike Schmidt looked at the balls Ted Williams played with, he’d be dismayed. If Ted Williams looked at the balls Babe Ruth had to hit, he would have been horrified.” Then there’s the issue of the armour a modern hitter like Barry Bonds wears so he can crowd the plate and not fear getting hit by a pitch. The Babe had no such advantage, (not even the muscular build-up). And he’d been on the field when Ray Chapman got killed by a pitch in 1920.

Another big point Jenkinson makes is the disappearance of the high strike in baseball. In Ruth’s time, the strike zone was called pretty much as the rules describe: from the letter to the knees. Now anything above the waist is “high”. Ted Williams once had trouble with a pitcher named Ellis Kinder. He finally got his first home run off him. He attributed it to the fact that Kinder had finally made the mistake of getting the ball down instead of “chest-level”. Ted said he “could not hit a ball squarely” if it were at chest level. But a chest level ball in those days was a strike. Now it’s a ball.

All-Around Player

Jenkinson also talks about how much of an underrated all-around player Ruth was. He read many accounts of great defensive plays Ruth made in the outfield and came across a quote by Tris Speaker calling Ruth “One of the greatest defensive outfielders I have ever seen.” The Babe was also an aggressive baserunner, stealing as many as 17 bases in a season and 123 in his career. He had ten career steals of home, seven inside the park home runs and 136 triples. The old films clips always show him trotting around the bases after a home run but he could really run. There are numerous accounts of his playing hurt or seriously ill. He virtually always played, knowing the fans came to see him. And the Yankees took advantage of that, scheduling exhibitions on every off day and on their trips north from spring training. With that and his barnstorming, the Babe played over 200 games a year. And, of course, he was a great pitcher who could have won 300 games if he’d kept at it.

Conclusions

The conclusion seems inescapable that Babe Ruth would be much greater today than he was in his own time, even as incomparable. Players that appear to have achieved as much or more are clearly not in his class at all. And he didn’t do it by using drugs to turn himself into a cartoon action figure. Doctors in his time tried to determine how he did do it. They determined that he had “abnormally thick wrists and forearms, high coordination, superior eyesight, hearing and ‘nerves’, (reactions), and a high degree of ‘perceptual intelligence’”. His chest when expanded was 7 inches wider than normal. The average is 2 inches. That’s supposed to be a sign of natural strength. I would use another term popular to modern commentators. I think the game just “slowed down” for the Babe due to his “perceptual intelligence” and he was thus able to do things other people could not do.

He was so superior to everyone in his own time that is was almost superfluous to study his accomplishments. He was Babe Ruth and nobody else was. His abilities and achievements never had to be carefully studied to marshal a defense against some challenger to his reputation. Instead his colorful, almost clownish personality was what people reacted to the most. That image was left with us and when other players under more favorable conditions matched or exceeded his records and it came to assumed that he was just a creature of his time, Grandpa’s hero, and had been caught and passed by the march of time. Bill Jenkinson has set the record straight, subtitling his book “The Recrowning of Baseball’s Greatest Slugger”.

(I used Jenkinson’s book, which is 412 pages long and discusses these things in much more detail while also including many personal anecdotes about the Babe’s life and personality. I highly recommended it be read in its entirety. Some of the numbers are my computations based on Jenkinson’s numbers. I also used other books Like “Green Cathedrals” and “Total Baseball” for some of the information.)

Nicknames

By the way, the Babe surely leads everyone in nicknames, as writers sought greater and greater hyperbole to describe this phenom. They included: The Ace of Clubbers, The Baltimore Adonis, The Bambino, The Behemoth of Bust, The Boston Mauler, The Caliph of Clout, The Goliath of the Bludgeon, The Grand Colossus of Hitters, The Heroic Figure of our National Sport, (has anybody called Barry that?), The Human Howitzer, The Jumbo Jouster, The Khedive of Klout, The Maharajah of Mash, The Mighty Man of Baseball, The Monarch of Maulers, The Potentate of Pounders, Ruthless Ruth, The Sultan of Swat, (my favorite), The Terror of Pitchers, The Titan of Thump, what Wali of Wallop, the Wazier of Wham, The Wizard of Wallop, The Emporer, Hercules, Samson, Superman, Tarzan and Zeus, among many others.

Last edited: